• Chronique par Tim Niland sur Music and More (29 décembre 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Tim Niland sur Music and More (29 décembre 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Sélectionné par John Sharpe parmi ses Best Releases of 2017 (28 décembre 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• European Scene par Peter Margasak (DownBeat, Janvier 2018)

Homegrown Intimacy

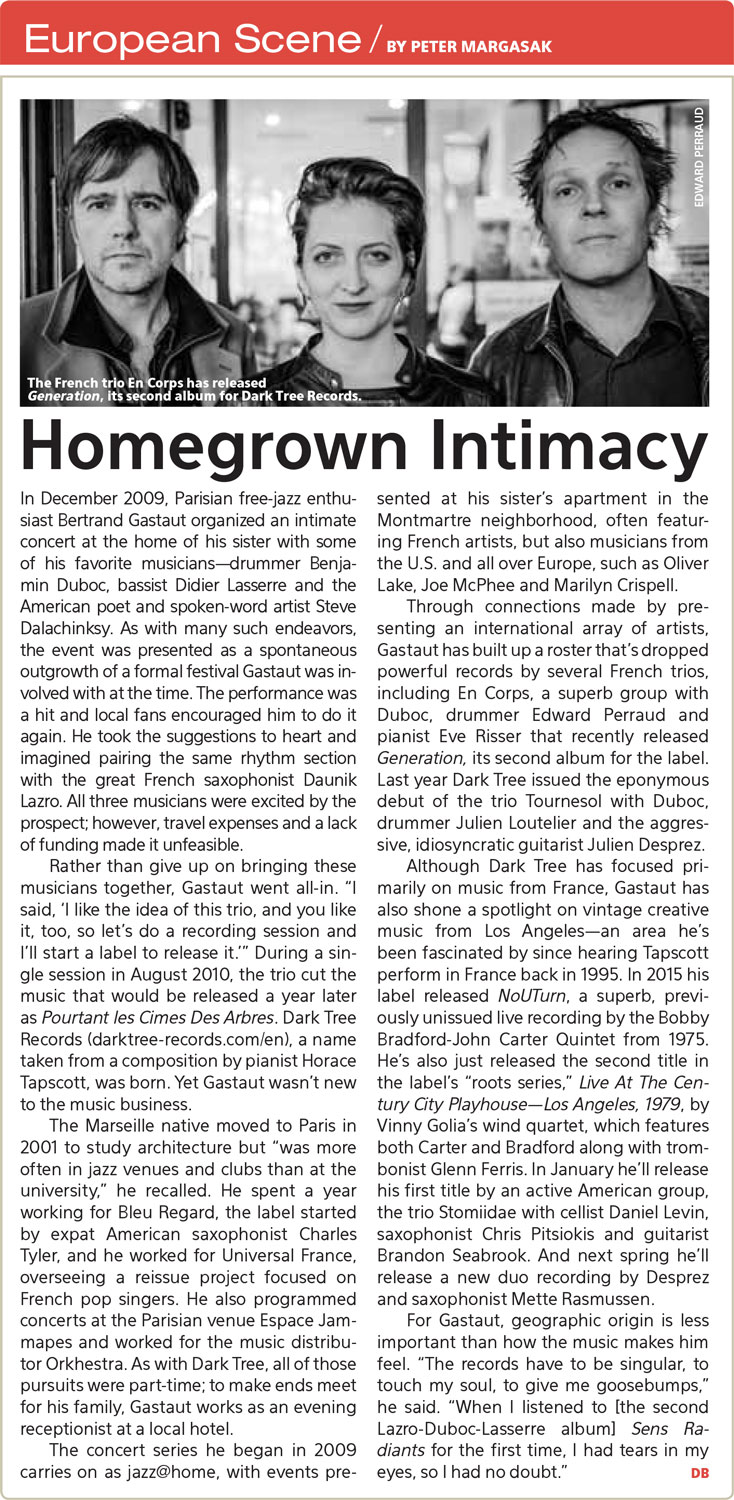

In December 2009, Parisian free-jazz enthusiast Bertrand Gastaut organized an intimate concert at the home of his sister with some of his favorite musicians—bassist Benjamin Duboc, drummer Didier Lasserre and the American poet and spoken-word artist Steve Dalachinsky. As with many such endeavors, the event was presented as a spontaneous outgrowth of a formal festival Gastaut was involved with at the time. The performance was a hit and local fans encouraged him to do it again. He took the suggestions to heart and imagined pairing the same rhythm section with the great French saxophonist Daunik Lazro. All three musicians were excited by the prospect; however, travel expenses and a lack of funding made it unfeasible.

Rather than give up on bringing these musicians together, Gastaut went all-in. “I said, ‘I like the idea of this trio, and you like it, too, so let’s do a recording session and I’ll start a label to release it.’” During a single session in August 2010, the trio cut the music that would be released a year later as Pourtant les Cimes Des Arbres. Dark Tree Records (darktree-records.com/en), a name taken from a composition by pianist Horace Tapscott, was born. Yet Gastaut wasn’t new to the music business.

The Marseille native moved to Paris in 2001 to study architecture but “was more often in jazz venues and clubs than at the university,” he recalled. He spent a year working for Bleu Regard, the label started by expat American saxophonist Charles Tyler, and he worked for Universal France, overseeing a reissue project focused on French pop singers. He also programmed concerts at the Parisian venue Espace Jemmapes and worked for the music distributor Orkhestra. As with Dark Tree, all of those pursuits were part-time; to make ends meet for his family, Gastaut works as an evening receptionist at a local hotel.

The concert series he began in 2009 carries on as jazz@home, with events presented at his sister’s apartment in the Montmartre neighborhood, often featur- ing French artists, but also musicians from the U.S. and all over Europe, such as Oliver Lake, Joe McPhee and Marilyn Crispell.

Through connections made by presenting an international array of artists, Gastaut has built up a roster that’s dropped powerful records by several French trios, including En Corps, a superb group with Duboc, drummer Edward Perraud and pianist Eve Risser that recently released Generation, its second album for the label. Last year Dark Tree issued the eponymous debut of the trio Tournesol with Duboc, drummer Julien Loutelier and the aggressive, idiosyncratic guitarist Julien Desprez.

Although Dark Tree has focused primarily on music from France, Gastaut has also shone a spotlight on vintage creative music from Los Angeles—an area he’s been fascinated by since hearing Tapscott perform in France back in 1995. In 2015 his label released NoUTurn, a superb, previ- ously unissued live recording by the Bobby Bradford-John Carter Quintet from 1975. He’s also just released the second title in the label’s “roots series,” Live At The Century City Playhouse—Los Angeles, 1979, by Vinny Golia’s wind quartet, which features both Carter and Bradford along with trombonist Glenn Ferris. In January he’ll release his first title by an active American group, the trio Stomiidae with cellist Daniel Levin, saxophonist Chris Pitsiokos and guitarist Brandon Seabrook. And next spring he’ll release a new duo recording by Desprez and saxophonist Mette Rasmussen.

For Gastaut, geographic origin is less important than how the music makes him feel. “The records have to be singular, to touch my soul, to give me goosebumps,” he said. “When I listened to [the second Lazro-Duboc-Lasserre album] Sens Radiants for the first time, I had tears in my eyes, so I had no doubt.”

• Chronique par Guy Sitruk sur Jazz à Paris (4 septembre 2017)

Un trio piano, basse, batterie qui a largué toutes les amarres de la tradition, du déjà vu. L’objet est ici une sensibilité extrême au moyen d’un langage radicalement neuf.

Des corps, des âmes : deux pièces pour dire une dualité, peut-être à fronts inversés.

« des corps » comme évanescent. Un piano proche d’un clavier de clochettes. Des frappes et des frottements à l’origine indécidable. Des rythmes semblables à des figures mélodiques …

Cet univers aux repères incertains nous fait tendre l’oreille, étire notre sensibilité. Les sollicitations auditives jaillissent de partout, délicates, continues. Le temps est aspiré. Au bout d’un quart d’heure, on se retrouve emportés dans une houle d’une formidable cohérence, où tout trouve une place exacte, comme préméditée, écrite. Un mouvement inexorable, mais des touches imprévisibles. Et vers la fin, un chant ample à la basse, des éboulis à la batterie. Les clochettes délicates reviennent. Un moment de pure poésie.

On aurait pu s’attendre à ce que cette seconde pièce, « des âmes », soit la plus éthérée : un pied de nez ! Si le piano distille des notes délicates, des bribes de lignes, quelques virevoltes comme suspendues … de la main droite, la gauche ressasse des grondements sombres ponctués d’éclats, de grands clusters plaqués avec violence. La basse offre en continu une deuxième voix aiguë (quel paradoxe!) toute en chants entremêlées avec les aigus du piano, alors que la batterie alterne affûts menaçants et martèlements puissants sur les peaux, les pièces de métal. Une pièce relativement courte (16 mn) qui nous laisse pantois.

Eve Risser (p), Benjamin Duboc (b), Edward Perraud (dr), trois créateurs aux filaments sensitifs particulièrement développés qui se croisent, se frôlent, se caressent, s’entremêlent, se libèrent, se rapprochent à nouveau. Un album particulièrement subtil et saisissant.

Je ne voulais pas écouter leur premier album pour comparer les univers sonores, pas plus que lire la chronique écrite alors (http://jazzaparis.canalblog.com/archives/2012/10/03/25235803.html).

Il fallait que ce second album opère seul.

Mieux, il fallait ne rien écrire avant que d’entendre cet opus à plusieurs reprises, parfois en commençant par la seconde pièce. La séduction, l’envoûtement n’en sont que plus fort.

Faut-il le préciser ? Encore un parcours sans faute du label Dark Tree dont chaque publication devient indispensable.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• ★★★★★ All About Jazz par John Sharpe (1er août 2017)

The eponymous debut En Corps (Dark Tree, 2012) by the French triumvirate of pianist Eve Risser, bassist Benjamin Duboc and drummer Edward Perraud made several year-end lists, and Génération belongs in the same category. Les Deux Versants Se Regardent (Clean Feed, 2016) by Risser’s White Desert Orchestra revealed her as a composer of note, as well as an innovative pianist, who resides in a line of explorers who have furthered John Cage‘s preparations for piano, such as Benoit Delbecq and Sophie Agnel. In addition to leading his own unit, Synaesthetic Trip, Perraud like Duboc remains a mainstay of the French improvising scene.

Risser may be one of the most percussive of pianists, operating habitually with a palette which evokes variously a gamelan, marimba, xylophone, and music box. Perraud convinces as an inventive purveyor of timbral variety, his efforts replete with well-reasoned embellishments and tight miniature figures which emerge unexpectedly and disappear again just as quickly. But it’s Duboc who keeps the show on the road, his resonant plucks, strummed flurries and humming bow work ensures that there’s movement when needed and imaginative stasis when not.

As a group their collective ethos places them firmly in a lineage which stretches from the trios of Bill Evans, Paul Bley and Howard Riley, through to the Portuguese RED Trio, Australia’s The Necks, and the NYC-based Dawn of Midi. The three like-minded principals spontaneously develop two extended cuts which make a virtue of careful judgment, restraint and sensitivity, while at the same time juddering on the launch pad, but never shooting for the stars. Why this stands out is the concentration in the moment which meticulously positions each sound both for its intrinsic value but also for its relation to others. While not quite consonant, the dissonances feel just right and the end result is mesmerizing.

« Des Corps » begins with a minimalist sonic painting of prepared piano, cymbal scrapes and arco murmurs which congeals into a pointillist portrait of great beauty. Exquisite and slow moving, bursts of unmodified piano suddenly sharpen into focus from modulated sonorities. Momentum gradually builds from the weight of individual components, with fleetingly reiterated patterns giving the sense an internal logic. At one point Duboc lends a Charlie Haden-esque gravitas and curdled lyricism, before becoming subsumed back into the flow. « Des Âmes » possesses more of an ominous undertow amid the thunder, as explosive drum outbursts, then Risser’s attacks hint at pent up energy before a prancing climactic flourish.

Many attempt to inhabit such terrain, but few can sustain it as well as these three.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Ken Waxman sur JazzWord (18 Juillet 2017)

Time-honored but tractable, the piano-bass-drums trio has been an intricate part of Jazz since the late 1940s, with its appropriately balanced triangle of sounds making it ideal for concepts ranging from Oscar Peterson’s precision to The Necks experimentation. Like Gallic reimagining of American film noir, two made-in-France trios are some of the most recent to expand on this formula. And like varied theories of viniculture each creates its product in a unique, though electrifying form.

The nine selections, almost all composed by pianist Roberto Negro, pulsate in an unusual fashion due to a couple of forceful; factors. For a start the cello of Valentin Ceccaldi takes the place of double bass in the program, confirming the instrumental prowess the Corsican string player has shown in other groups, including those featuring his bother violinist Théo. More crucially, Negro, born in Turin to Italian parents, while brought up in France, has composed a work that echoes his father’s wartime and post-bellum experiences. Added to the interpretations are a sound bite of the older man reminiscing on the concluding “Rosina cavatappi”, plus on the appropriately titled “1944” a scratchy recording of “Le Marche de Menilmontant”. Unassuming drummer Sylvain Darrifourcq rounds out the band.

As early as “Suole di gomma Vibram” the hectic concept of heroism and endurance is established by the writing of the pianist, who also works with a theatre company, as kinetic keyboard tones accelerate along with string bumping from the cellist and hard drum accents, leading to a concept both foot tapping and dramatic. Evolving with alternating elevated and subdued textures, conjoined pieces such as “Farina, crusca e voto alla Madonna” and “Camouflage, parte seconda” swing enough with a keyboard combination of glissandi and hunt-and-peck focus, to work out of the Red Garland-Wynton Kelly bag, while latterly post-modern reconstitutions take the merry melodies apart with dynamic piano key slaps and knife-like whines from cello strings.

Father Negro’s reminiscences, followed by protracted silences and quiet connective tissue of key sprinkles and string vibrations, operate like a film dissolve, leaving the listener yearning for more music. Yet the defining climax arrives with the penultimate “Grilletto”. Hearty cymbal sizzles intensify the dramatic earnestness of the piece which repurposes the melody to reflect power and passion via Negro’s kinetic rolls and Ceccaldi’s buzzing counterpoint.

The piano and bass playing on En Corps Generation are similarly intense and passionate with Eve Risser and Benjamin Duboc respectively, playing those roles, with drummer Edward Perraud having mastered everything from Rock-directed to microtonal sounds confirming his necessary intersection in this triangular outflow. Recorded in concert this second outing of the trio, consisting of three French players who have distinguished themselves in situations ranging from microtonal to raucous and from orchestral to solo, has as its focal point the nearly 33-minute “Des Corps”. Unfolding as slowly as a blossom in real time, the pianist’s initial out-of-tempo exposition is quickly deconstructed into brittle key chopping as all the while bow slides from Duboc and unexpected accents from Perraud provide thematic continuum. Midway through, Risser inventively breaks up the time with a series of clanking patterns and persistent key fanning until knuckle-duster-like pops from the drummer leads to woody, pressurized theme extension from the bassist. This strategy leads to a crescendo of ring-around-the-rosy impulses as each passes the narrative along like participants in a relay race. Eventually as the bassist brings cello-resembling, below-the-scroll slides into the company of broad keyboard expression alongside occasional percussion crunches, the three expel a nimble upwardly mobile finale. More theatrical, “Des Âmes”, the encore heightens the action with buzzing string scrubs, relentless percussion clattering plus glissandi that suggests a centipede racing across the piano keys. With this interaction both slick and solid as the piano and double bass lock into a groove the concluding sequence turns agile and humorous retaining good feeling among distilled bravura exhibited by players at the top of their game.

As long as trios such as these are around it appears that the varieties of sounds produced by piano-drums-and low-pitched string combos remain limitless.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• ★★★★ Jazzthetik par Henning Bolte (Juillet/Août 2017)

Repetitive minimaoistische Musik hat ihre ganz eigenen Eigenschaften. Ihre Wirkpotenziale entwickeln sich kumulativ aus dem Zusammenspiel von Wiederholung und Verschiebung, liegen jenseits des tatsächlich Gespielten. Eine spezielle Spielart des Minimalismus ist die Musik von En Corps – Generation. Die Wirkung entsteht hier daraus, dass die Musik einfach geschieht und dabei im Zuhören – ähnlich dem wahrgenommenen Geräuschgeschehen und Klangbild in einem Naturraum – Zusammenwirkungen entstehen. Es ist ein Ansatz, der sich in jeweilig anderer Ausarbeitung und Ausprägung auch bei dem australischen Trio The Necks und dem norwegisch-französischen Quartett Dans Les Arbres findet. Die französische Dreiereinheit von Risse/Duboc/Perraud (Piano, Kontrabass, Schlagwerk) ist mit einigen Jährchen unterwegs ein gut eingespielter Organismus. Die Musik ihres zweiten Albums besteht aus zwei qua Länge und Charakter deutlich unterschiedlichen Stücken. In abwechselnder Herausgehobenheit der drei Instrumentenklänge setzt das 37-minütige « Des corps » sehr allmählich sich verdichtende Klangzeichen um ein ungreifbares Zentrum herum. Es wirkt fast wie eine Freilegung von verborgenen Konturen. Das 17-minütige « Des âmes » dagegen ist weitaus bewegter, disruptiver, heftiger und entladender. Es wirkt wie Wärmewellen und Temperaturmischungen. Letztlich sind es die Klänge selbst, die das Werk verrichten. Bei aller Reduziertheit schöpfen die drei Musiker maximal aus ihren gesamten Spielerfahrungen. Dass es sich bei der Musikereinheit um ein Pianotrio handelt, merkt man bei alledem nicht – und das dürfte gut so sein.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Felix dans freiStil (Juillet-Août 2017)

Auf Wiederhören, En Corps! Eines der, wenn nicht überhaupt das Highlight der St. Johanner artacts ‘16 findet hier die Dokumentation. Zwei Stücke haben Risser/ Duboc/Perraud für generation ausgewählt. Das erste, des corps genannt, erzählt die Geschichte eines klassischen, wenn auch individuell verschobenen, verschrobenen Crescendos, die Erzählung einer Aufwallung, einer Schwellung. Was mit Eve Rissers zarten, pointillistischen Klavierklangverfremdungen beginnt, wird von Benjamin Duboc mit stoischer Ruhe kommentiert, während es da drüben bei Edward Perraud ein bissel scheppert. Noch ist nichts passiert. Heftigkeit und Hektik nehmen sukzessive zu, bringen Rissers schrittweise bordendes bis überbordendes Spiel immer noch genauer auf den Punkt, auf die Linie, auf die Fläche, in den Raum. Duboc bleibt Stoizist, alte Jimmy Garrison-Schule. Dafür gerät jetzt einer komplett aus dem Häuschen. Oh, Perraud! Stück zwei, des âmes, greift gleich mit Hurra ins Klavier, Rücksicht aufs Material unnötig, das Eingemachte ist bald umzingelt, es wird wohl zum Herauskommen gezwungen werden. Die Soundqualität, nebenbei gesagt, ist hervorragend transparent (Charles Wienand, guter Mann). Perraud swingt und drischt, dass es eine Freude ist; man sieht ihn förmlich auf und ab hupfen dabei. Risser gibt der Beute am Ende den Rest. Fantastique, wie wir Französinnen sagen. Die Einschätzung von damals liegt gar nicht so weit daneben: „Permanent brodelnde, nie abkühlende, immer auf hoher Flamme gehaltene Improvisation. Freejazz mit viel Luft, Fantasie und bezwingender Logik.“ Eine gnadenlose, gnadenlos schöne Musik!

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Recommended New Releases dans The New York City Jazz Record (Juillet 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Guy Peters sur Enola (6 avril 2017)

Het album zette meteen ook het kleine Franse label Dark Tree op de kaart, dat met zijn tweede release meteen kon rekenen op een groot succes (opnieuw, naar de normen van het wereldje). Het label deed het sindsdien rustig aan en brengt met Generationzijn zevende release uit. De muzikanten zaten intussen niet stil. Perraud was onder meer bezig met Das Kapital en The Fish, terwijl Duboc ook deel uitmaakt van The Fish en nog een paar keer van zich liet horen op het Dark Tree-label.Ook Risser was opvallend actief. Naast haar lidmaatschap bij onder meer het Orchestre National Du Jazz en een paar straffe ensembles van Pascal Niggenkemper, maakte ze ook een fraai statement met een soloplaat (Des Pas Sur La Neige, 2015) en vooral met haar White Desert Orchestra, waarmee ze grote sier maakte en een gelauwerd album uitbracht bij Clean Feed. In tegenstelling tot de debuutrelease is Generation geen studioplaat, maar een liveopname, in 2016 gemaakt tijdens het Artacts festival in Oostenrijk.

Meteen vallen een paar gelijkenissen op. Ook dit album bevat twee stukken, waarvan het eerste ruim over het half uur gaat en een (redelijk sterk verschillend) tweede stuk “beperkt” blijft tot een goed kwartier. In “Des Corps” kiest het trio resoluut voor een geduldige, grotendeels introverte aanpak, die opnieuw duidelijk maakt dat het hen niet te doen is om boude statements of makkelijk scoren. De gedempte noten van Rissers geprepareerde piano, de iel klagende, gestreken bas van Duboc en de frutselpercussie van Perraud maken snel duidelijk dat het gaat om texturen, kleuren en nuances, ideeën die gedoseerd op een canvas gedruppeld worden.

Het is verleidelijk om de link te leggen met schilderkunst, met lijnen en punten en arceringen die toegevoegd worden, met aandacht voor ruimte en dosering, tot er zachtjesaan een web van connecties ontstaat waarin de individuele lijnen misschien moeilijk te ontwaren zijn, maar het totaaloverzicht wel overtuigt. Er zit geen waarneembare puls in, geen duidelijke vorm of richting, er is enkel de interactie die zich ontwikkelt met een haast autistische vastberadenheid en aandacht voor details. Eerst open en kaal, daarna iets drukker en volumineuzer. Het heeft hier en daar een zekere nukkigheid, die na een kwartier omslaat in een haast mechanische flair die een steeds sterker trance-effect krijgt.

Het is ook sterk repetitief, met als meest voor de hand liggende verwante de obsessieve spanning van The Necks. Er duikt ook een knap moment op wanneer Duboc, die dan al even wat krachtiger met de vingers plukt, het zeil naar zich toetrekt met een fraaie solo, waarna het stuk gradueel uitdunt en stilvalt met merkwaardige klanken. Die steken opnieuw de kop op in “Des Âmes”, dat grover, krachtiger en donkerder klinkt. Er zit een onderhuids gedaver in, het is een minder geruststellende wereld, waarin uitvallen van Perraud opduiken als ritmische aanslagen en een puls als een kloppende ader de sfeer dicteert. De piano wordt hier ook resoluut uitgespeeld als een klankenmachine. Je gaat je afvragen of en in welke mate het instrument beschadigd werd tijdens het concert.

Vermoedelijk valt dat allemaal mee, maar de bekommernis zegt misschien wel iets over de impact van dit trio, dat zowel in zijn ascetische als voluptueuze bewegingen erin slaagt om maximale vrijheid in evenwicht te houden met een intuïtieve samenhang, die ook nu weer leidt tot een expansieve, soms zelfs bedwelmende luistertrip.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Aleš Rojc sur Radio Student (4 juin 2017)

Hecno je soočati zvokovja bendov, kakršen je trio En Corps, z nekaterimi zapisi o tem projektu, saj človek iz slednjih hitro dobi vtis, da posluša enega od stranskih projektov pianistke Eve Risser. Ta je tudi iz kolega Zormana uspela izvabiti kar nekaj poetičnih zapisov in rezultat je, da smo z nedavnejšim delom opusa omenjene mojstrice prepariranega klavirja na teh frekvencah dobro seznanjeni. Če na primer začnemo s primerjavo z njenim predlanskim solističnim izdelkom, Stopinje v snegu, se velik del prve polovice posnetka tria sliši kot razširitev njenega klavirskega zvoka s še dvema soigralcema. A če vseeno triu ne želimo storiti prevelike krivice, velja izhodišče nekoliko prirediti in tokratno zasedbo vzeti za takšno, kot je, torej za trio.

En corps na svojem drugem posnetku izkoriščajo besedno igro svojega imena, kar v tem primeru pomeni namigovanje na telesnost, neusihajočo tenzijo po nadaljevanju in morda še kaj. Sicer pa so precej navdušili z zdaj že pet let starim prvencem. Recimo, da trio v vodah improvizirane muzike navdušuje na dva načina. Bodisi s poudarjeno jazzovsko igro prikliče duha nebrzdane svobode in v trenutku napolni srca specializirane publike, ki išče in najde nemalo vzporednic s tem ali onim herojskim koščkom jazzovske zgodovine. Ali pa z nekim momentom, ki se mu pač nekako uspe splesti v čarovnijo skupinske igre, ki bolj neposredno nagovori zunaj specializiranega idioma – pa četudi je v slednjem primeru verjetnost, da bo s tem presegel jazzovske kroge, majhna. A tu gojimo iluzijo, da le zato, ker se muzike, kakršne podaja En corps, pač težko znajdejo kje drugje kot na odrih specifičnih klubov ali jazzovskih festivalov. Kakršen je bil sicer tudi lanski ljubljanski jazzovski festival z En Corps na programu.

Trio na svojem drugem posnetku nadaljuje pot, kakršno je začrtal pred petimi leti. Dva improvizirana kosa, daljši in krajši, ki ne vpeljeta nobene teme, a v katerih že sama razporeditev zvoka zveni kot tema zase. In ta se nam razodene skozi različne dimenzije. Lahko na primer opazimo, da gre za muziko, ki je vseskozi v razmerju s tišino in svoje niti razvija zelo počasi, še raje kar v suspenziji časovnega poteka. V tem primeru v ospredje pride barvajoči odzven enega klavirskega tona, ki pulzira iz celotne slike in jo zavrti v nek svoj, zaprti svet impresionistične kompozicije, ki je na starejšem posnetku posrečeno prejela ime trans. S tega vidika so Generacije, ki jih predstavljamo nocoj, triu bolj naklonjena oblika. Čeprav je težko razločiti, kje se odzven strune odprtega klavirja loči od pridušenega vibriranja strune kontrabasa ali škripanja činele, pa vemo, da tudi v subtilnejših trenutkih poslušamo vse to.

Iz nekega drugega zornega kota, ki je tudi stalnica triovih kompozicij, pa se zadeve sicer dramatično razvijejo, a še vedno na nekoliko paradoksalen način. Nežno in počasno tipanje daljšega kosa z naslovom Telesa se zelo počasi in komaj opazno prevali v divjo in nebrzdano igro, ki pa bi jo še vedno težko primerjali s svobodnjaškimi jazzovskimi kolektivizmi. Morda je primerna opazka avtorja z bloga Allaboutjazz, ki v taki igri prepozna poudarjeno disciplino in natančnost orkestrov Sun Ra-ja, katerega muziko sicer tolkalec Edward Perraud raziskuje v nekem drugem projektu, Supersonic. V tem primeru se disciplina tria En corps le ne izrazi na isti način.

Tudi ko se igra prevesi v brundasto godeč basovski solo Benjamina Duboca, in četudi poklonom različnim virom iz ozadja ves čas pritrjuje bobnar Edward Perraud z nekakšno kombinacijo divjosti in umiritev, En corps ostajajo zvesti svojemu pridušenemu grajenju zvena, ki zunaj frazeoloških ponovitev ostaja nenavadno dostopen.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• ★INDISPENSABLE★ par Mathias Kusnierz dans Jazz News (juin 2017)

Le deuxième album du trio En Corps (Risser au piano, Duboc à la contrebasse et Perraud à la batterie) est l’enregistrement d’un concert donné au festival Artacts en 2016 en Autriche. Ces deux longues pièces improvisées, dans l’esprit de leur excellent premier album paru sur Dark Tree en 2012 (et qui vient d’ailleurs d’être repressé), mêlent en un tissu serré pulsations en pagaille, moments d’intensité bruitiste lorsque Eve Risser martèle ses graves pendant que Benjamin Duboc fait rugir son archet, et brèves accalmies percussives et arythmiques guidées par le piano préparé. À chaque instant jaillit une énergie à la fois inextinguible et incontrôlable, si ce n’est par l’intelligence du temps musical et des timbres que manifeste le trio.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• ★★★★ JazzMagazine par Vincent Cotro (juin 2017)

Après un premier album paru en 2012 sur le label DarkTree, le trio En Corps propose ici une captation live sous la forme de deux longues improvisations. Des âmes (presque 17 minutes) s’ouvre par une longue “entrée en matière” grouillante, grondante, inquiétante, où personne n’est là où on l’attend ni l’entend.

Des sonorités de piano préparé proches parfois d’un gamelan, des textures aux origines improbables, des notes répétées sans but apparent (bizarrement, le jeu d’Ève Risser et le son d’ensemble me rappellent parfois l’Ellington de “Money Jungle”…) Puis une lente éruption mène au déferlement d’une lave ici compacte et solide, là brillant d’éclats plus furtifs ou expulsant d’inouïes flammèches. L’enregistrement d’une telle performance soulève, ici comme ailleurs dans l’improvisation radicale, le problème du tout que forme la “musique” avec les gestes et la présence des corps à l’œuvre et dont l’observation nous fait ici défaut. Restent pourtant de véritables instants de grâce et de poésie sonore, comme ceux qui parsèment le premier quart d’heure de Des corps, long crescendo parti de rien, où le silence agit comme un quatrième musicien pour lentement irriguer et lier les événements surgis de toutes parts. L’attention portée à chaque détail et chaque geste (du frôlement au fouettage des matières percussives, de la trituration hypnotique de la corde à l’extraction patiente des bribes mélodiques tapies dans les accords ressassés) se relâche et s’intériorise dans le temps long ainsi exploré, et la magie opère même (et surtout) sans les yeux.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

DISPONIBLE MAINTENANT : EN CORPS – GENERATION (DT07)

À NOUVEAU DISPONIBLE, LEUR PREMIER ALBUM : EN CORPS (DT02)

OFFRE SPÉCIALE, EN CORPS (DT02) + EN CORPS – GENERATION (DT07) : – 25% !!

EVE RISSER • BENJAMIN DUBOC • EDWARD PERRAUD

EVE RISSER • BENJAMIN DUBOC • EDWARD PERRAUD

EN CORPS – GENERATION

EVE RISSER piano

BENJAMIN DUBOC contrebasse

EDWARD PERRAUD batterie

01 | des corps |

02 | des âmes |

cliquer ICI pour écouter 2 EXTRAITS

DT 07

15 € FRAIS DE PORT INCLUS

OFFRE SPÉCIALE : DT02 (voir plus bas) + DT07

22,5€ FRAIS DE PORT INCLUS

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Andrzej Nowak sur Jazzarium.pl / Spontaneous Music Tribune (24 mai 2017)

Fakty są bezsporne. Muzyka swobodnie improwizowana ma się we Francji wyśmienicie. Czasami, szukając przymiotnika dotyczącego tego akurat zakątka świata, używamy – przynajmniej w kulturze bardziej masowej, by nie rzec… sportowej – określenia Trójkolorowy. Bingo! Najlepsza muzyka, jaka ostatnio tam powstaje, ma na ogół wymiar… trzyosobowy, a mieni się nawet większą ilością kolorów! Wnikliwy Pan Redaktor dostrzega jeszcze dwa inne zjawiska, które na ogół towarzyszą eksplozjom doskonałego free improv nad Sekwaną.

Najpierw kontrabasista Benjamin Duboc! Czego się nie tknie w ostatnich latach, perły wychodzą.

O płytach tria Daunik Lazro/ Benjamin Duboc/ Didier Lassere pisaliśmy na Trybunie wyłącznie złotą czcionką (Pourtant Les Cimes Des Arbres 2011, Sens Radiants 2014) patrz tutaj. Nie inaczej było w przypadku ekscesu pod nazwą Tournasol (2016) patrz tutaj. Duboc dobrał tu do trójki piorunującego gitarzystę Juliena Despreza i jego imiennika, perkusistę Louteliera.

Dziś czas najwyższy, by poznać kolejne trio z udziałem Duboca, a także dwa jego dotychczasowe wydawnictwa. W tym układzie personalnym za zestawem perkusyjnym zasiądzie jego rówieśnik i muzyk, choć trochę już uznany w światku niszowej muzyki bez melodii – Edward Perraud. Składu zaś dopełni Eve Risser, pianistka o dekadę od nich młodsza, która w cuglach podbija obecnie świat muzyki improwizowanej, a zbiór oponentów wobec tej tezy przyjmuje trwale wartość zerową.

Za wydanie wszystkich tych płyt odpowiada jeden człowiek. Nazywa się Bertrand Gastaut i od kilku lat prowadzi wydawnictwo Dark Tree Records.

En Corps – edycja pierwsza

Marzec 2012 roku. Studio nagraniowe w Malakoff/ Francja. Akustyczne trio w mało wyszukanym układzie instrumentalnym – fortepian (preparowany i … niepreparowany – cytuję za okładką), kontrabas i perkusja. Muzycy będą improwizować przez 51 minut, w dwóch odcinkach, a na płycie znajdziemy to jako En Corps (Dark Tree Records, 2012).

Trans. Pianistka Eve Risser rozpoczyna tę opowieść pojedynczymi akordami z klawiatury, wspierając się delikatnym szarpaniem strun z głębi swego wielkiego instrumentu. Kontrabasista Benjamin Duboc, wyposażony w długi smyczek, sunie głębokim soundem tuż pod nią. Perkusista Edward Perraud, w reakcji na poczynania interlokutorów, stawia systematyczne stemple i niezobowiązująco tyczy granice tej bardzo zrównoważonej i dostojnej niemal narracji. Wnikliwa wyobraźnia słuchacza dostrzega jednak zaszyty w niej nerw moralnego niepokoju i stygmaty tajemniczości. W wymiarze akustycznym rządzi tu zdecydowanie Duboc, zajmując trzy-czwarte przestrzeni dźwiękowej. Perraud ciekawie sonoryzuje na krawędzi bocznego toma, a Risser (jest już chyba wewnątrz instrumentu) sprawia wrażenie, jakby grała na … wiolonczeli. Delikatna dynamizacja poczynań całej trójki efektownie wzmaga jakość improwizacji. Perkusista zaczyna drżeć, wibrować wokół własnej osi, a kontrabasista dodaje mu rezonu, schodząc z brzmieniem coraz niżej (od paru chwil jest już w piwnicy). Pianistka aktywizuje skromny, acz intensywny pasaż wprost z czarnobiałej klawiatury. Dźwięki wszystkich instrumentów lepią się do siebie, jak plastry lipowego miodu. Choć każdy z muzyków gra trochę inaczej, to jesteśmy już w trakcie zwartej, spójnej i intensywnie symbiotycznej galopady (trans!). Benjamin krwistym smykiem wyżłobił już w podłodze rów mariański! Demokracja w zespole wszakże kwitnie w najlepsze. Około 19 minuty narracja delikatnie rozwarstwia się, muzycy łypią na siebie spode łba i w mgnieniu oka… eskalują kolejną, jeszcze bardziej wyrazistą improwizację w narowistym tempie. Eve gra tu mało, ale każdy jej dźwięk jest uzasadniony i zdobi wyczyny sekcji pięknymi, złotymi girlandami. Po 26 minucie smyczek idzie w odstawkę. Narracja robi się gęsta, jak sos do kaczki. Z klawiatury sunie, wprost w nasze uszy, niebanalna literatura, która wieńczy słoną eskalacją, ów ważny fragment historii improwizacji francuskiej.

Chant D’entre. Uspokojenie, budowane wyważonym dronem, płynącym wprost z paszczy trójgłowego smoczyska. Polerowanie powierzchni płaskich, akordy piana zza siódmej góry. Bijące serce perkusji szuka rytmu, jest agresywne, nadaktywne, odrobinę zbyt głośne. Kontrabas idzie z czarnej głębi, poszukujący, niezdecydowany (bić się, czy uciekać?). Perraud ma depnięcie trochę, jak Tom Bruno z Test, ale nie stroni od sonorystyki. Ten fragment płyty toczy się przy podobnym zagęszczenia incydentów akustycznych, jak pierwszy, ale w uwagi na niższą dynamikę, daje sposobność słuchaczowi na swobodnie wgryzanie się w zamysły muzyków i czerpanie dodatkowych porcji przyjemności. Narracja jest jakby zawieszona w powietrzu, płynna, tajemnicza, nieoczywista. Eve zdobi ją kilkoma zmyślnymi preparacjami w pudle rezonansowym. Jest tak rozbrajająco niejazzowa. Śle partnerom nielinearne pasaże do przemyślenia, nieco w poprzek rytmu, który wyznacza ordynarna stopa zestawu perkusyjnego (8-9 minuta). Tuż potem Benjamin włącza drapieżny walking i też postanawia postawić trwały ślad na ziemi w ramach tej eskapady. Eve podłącza się, jak sroczka i łapie odpowiedni dryl. Finał nagrania jest nagły, zerwany. W taki sposób, byśmy natychmiast poprosili o więcej!

En Corps Generation – edycja z oklaskami

Mijają cztery lata. Znów jest marzec. Nasza trójka bohaterów aktywnie wypoczywa w Tyrolu, w Austrii. Sobota, sala koncertowa (?), Artacts’16. Improwizacja odbędzie się z udziałem publiczności i potrwa 55 minut (znów dwie części). Wedle wskazań okładki, Eve Risser będzie grała na fortepianie (brak dodatkowych wskazówek, zwłaszcza w zakresie ewentualnych preparacji), jej męscy partnerzy – bez zmian. Płyta dokumentująca wydarzenie koncertowe jest z nami od kilku tygodni i zwie się En Corps Generation (Dark Tree Records, 2017).

Des Corps. Start jest spokojny, pełen wewnętrznej ciszy, toczony z dbałością o szczegóły, pojedyncze interakcje. Tu kropka, tam przecinek. Muzycy nawołują się na skraju puszczy, bo już czas ruszać po złote runo. Akord, talerz, akord, stopa. Eve płynie tylko po klawiaturze, tak, jak obiecała przed chwilą. Gra nieco inaczej, niż w studiu, cztery lata temu. Mniej rytmiczna, bardziej separatywna w zachowaniach scenicznych, pozostawia mokre ślady na scenie (wzrost świadomości artystycznej?). Edward, niczym doświadczony suwnicowy, snuje oniryczne pojękiwania. Benjamin ewidentnie przyczajony, smyczek w dłoni, jest wyrazisty i czeka na sygnał. Wszyscy macają się w ramach gry wstępnej. Narracja jest powolna, wręcz majestatyczna. Ale jednak się dzieje. Jakby każdy dźwięk był odrobinę silniejszy od poprzedniego. Akustycznie bardziej dobitny. Klimat tej piosenki bliższy jest drugiemu fragmentowi z debiutanckiej. Nawarstwianie się płaszczyzn improwizacji następuje tu jakby mimochodem. Po 15 minucie akordy stają się cięższe, dynamika eskaluje step by step, interakcje są szybsze, bardziej dosadne i uszczypliwe. Duboc rytmizuje proces improwizacji, jest nawet pokrętnie rockowy. Mimo wszakże drobnych różnic w doborze środków wyrazu, to trio ciągle przypomina trójgłowego potwora ze studyjnego incydentu sprzed kilku lat. Empatia? Synergia? – wciąż poziom ponadnormatywny. Risser jest może bardziej wyrazista narracyjnie, choć recenzent nie jest do końca przekonany, że bardziej oryginalna. Tu i teraz gra więcej, w zasadzie nie preparuje dźwięków, choć roli dodatkowego perkusisty nie odrzuca definitywnie. Być może ta generacja Er Corps jest bardziej efektowna, w większym stopniu przyswajalna dla jazzowego odbiorcy, ale … recenzent już tęskni za jej prymalną inkarnacją. Po 20 minucie pierwszy odcinek koncertu wpada w ciekawą galopadę. Lekkie wyhamowanie stymulowane jest przez melodyczny kontrabas, przy wtórze szczoteczkowania perkusji (to jednak prawie solo strunowca). Fortepian milczy, ale perkusja wpada w turbulencje. Na finał fragmentu, Eve powraca w szorstkich klimatach pierwszej płyty. Benjamin uroczo smykuje, a Edward zawiesza się dramaturgicznie. Brzmienie dźwięków z klawiatury jest matowe, delikatnie przybrudzone (z kajetu recenzenta: najpiękniejszy fragment tej płyty!).

Des Ames. Giniemy w tumulcie oklasków, na szczęście ciąg dalszy następuje, głównie dzięki mocnym akordom piana (chyba jednak drobna preparacja!), które skutecznie zagłuszają incydenty akustyczne na widowni. Wodogrzmoty Mickiewicza z gryfu kontrabasu. Mały suwnicowy na prawej flance. W aurze jakże wytrawnej sonorystyki, śmiało możemy zapaść się w drugą część koncertu. A ta stymuluje nasze endorfiny. Cierpimy z satysfakcji! Narracja piana zagęszcza się. Duboc podaje krwawy walking. Perraud zaczyna niewybrednie hałasować. Agresywne dźwięki każdego z instrumentów frasobliwie lepią się do siebie (oj, będzie chleb z tej mąki!). Risser jakby trzaskała klapą fortepianu, miażdżąc palce widzów w pierwszym rzędzie. Gdy nominalna sekcja gna i tupie, pianistka podaje lekko splątaną, frapującą palcówkę. Niemal swoich facetów zagaduje, tak w pół słowa. Czyżby i ją dopadały już natręctwa rasowej pianistki free? W odpowiedzi dialog Edwarda i Benjamina. Szukają kąśliwego zakończenia. Ten pierwszy uruchamia dzwonki (już czas! już czas!). I cała trojka biegnie na szczyt! Jeszcze tylko drobny ornament z werbla i końcowy orgazm staje się udziałem wszystkich! Hałas z drugiej strony sceny trwa kilkaset sekund.

Szczególnie ekscytujący jest dokument fonograficzny koncertu, jaki odbył się w Pasadenie, lat temu… czterdzieści dwa! Wspólny kwintet Bobby Bradforda (kornet) i Johna Cartera (klarnet, saksofon sopranowy), z udziałem dwóch kontrabasów (Roberto Miranda, Stanley Carter) i jednego zestawu perkusyjnego (William Jeffrey). Płyta No U-Turn – Live in Pasadenia, 1975 (Dark Tree Records, 2015) jest porażającym dowodem na nieśmiertelność free jazzu tamtej epoki. Lektura obowiązkowa w każdym porządnym domu.

Ostatnią z niewymienionych dziś pozycji katalogowych francuskiego labela jest duet niepowtarzalnej Joelle Leandre (kontrabas) z poetą użyczającym głosu, Steve’m Dalachinsky’m. Koncert z maja 2012 roku, z Paryża, odnajdziecie pod tytułem The Bill Has Been Paid (Dark Tree Records, 2013).

Ps. Tłumaczenie tytułu posta dla mniej obytych lingwistycznie – Wszystko o Ewie… i Benjaminie, i Edwardzie (ang.). Trzy kolory rządzą! (franc.)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Franpi sur Sun Ship (18 mai 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Jean-Michel Van Schouwburg sur Orynx (16 mai 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Europe Jazz Media Chart (Mai 2017)

Sélectionné par Anne Yven, Citizen Jazz (France)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Recommended New Releases dans The New York City Jazz Record (Mai 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Tim Niland sur Music and More (1er mai 2017)

This was a very interesting two-part live improvised session with Eve Risser on piano, Benjamin Duboc on bass and Edward Perraud on drums. The music is very spacious and the musicians use everything at their disposal to interact with one another and create some very interesting sounds. « Des Corps » is the first track on the album, and it is a very long collective improvisation, over thirty-seven minutes in length. The trio is playing at a very high level throughout the performance, with Risser making use of the length and breadth of the piano, playing in the standard manner and using extended techniques to increase the music making opportunities available to her. It is interesting to listen to the bass and drums interface with the piano, with bowing and scraping and fractured beats and rhythm allowing the music to develop organically, with the interaction between the instrumentalists coming in an unforced and original manner. Things get even more interesting on the concluding track, « Des Âmes » where the music grows darker and much more intense. The piano, bass and drums develop a storming collective improvisation which incorporates some slashing drumming, arcing and buoying bass playing and thunderous squalls of notes and chords from the piano. The trio really goes for broke here, complementing each other very well, and allowing the music to develop as a complex and multi-layered thing that nearly takes on a life of its own, leading to some exuberant and aggressive interplay between piano and drums with the bass riding point. The three players encourage one another on to greater exploratory heights with strong musical technique on ready display. The music develops various hues throughout the performance with dark and ominous sounds giving way to rays of sunlight as the improvisations develop and the musicians explore a wide open soundscape, culminating with a lengthy round of well deserved applause from the audience. This was an enjoyable and very well played album, and should be of particular interest to fans of European free improvisation.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Andrzej Nowak dans Jazzarium.pl / Spontaneous Music Tribune (24 avril 2017)

Spotkali się w poniedziałek 19 stycznia, dwa lata temu, w Ackenbush, Malakoff (piszą, że to we Francji). Nagrali niezbyt długi materiał. Takie duże pół godziny. Po roku z okładem – dzięki francuskiemu wydawcy Dark Tree – muzyka ujrzała światło dzienne. Dziś, gdy mija kolejny rok, po raz wtóry chwytam po ten krążek i mam nieodpartą chęć, by wreszcie podzielić się z Wami wrażeniami z odsłuchu.

Trzech młodych (lub średnio młodych) francuskich improwizatorów. Z nazwiskiem Duboc być może nieliczni z Was mieli okazję się zetknąć, albowiem jego dyskografia śmiało przekroczyła dziesięć pozycji (osobiście cenię go szczególnie za świetne nagrania z Daunikiem Lazro). Gra na kontrabasie. Ten pierwszy – Desprez – to gitarzysta, głównie elektryczny, z pewnością muzyk silnie poszukujący nieoczywistych rozwiązań, które tak bardzo cenimy na tych łamach (ważny trop dla tych, którzy słuchając muzyki improwizowanej wciąż brną w te same nazwiska – grał na płycie Fire! Orchestra). Ten trzeci – Loutelier – perkusista, niemal pusta kartoteka, jeśli chodzi o muzykę improwizowaną. Zagrali świetną płytę w trio. Zasiali zamęt w mojej głowie. Jeśli chcecie poznać szczegóły, zapraszam poniżej.

Pour que. Kontrabas uzbrojony w dobrze naostrzony smyczek, rwie połać podłogi studia nagraniowego. Wtóruje mu szemrzący zestaw perkusjonalisty i milcząca na pozór gitara, która dzięki skromnym manipulacjom na kablach, tudzież wymuskanych potencjometrach, zyskuje prawa do współtworzenia dźwięków otwarcia tego albumu. Instrumenty zgrabnie łączą się w sunący dość nisko wielodźwięk, który zwyczajowo zwykliśmy określić mianem drona (mimo ciągłego naużywania tego określenia w ostatnich tygodniach na Trybunie). Smakuje tu elektroniką, której ktoś odciął prąd. Panuje akustyczny zgiełk, którego mikroelementy pędzą w tym samym, acz zupełnie nieznanym nam kierunku. Ów wielodźwięk narasta, jest spójny, pełnokrwisty, wręcz noisowy. Choć jesteśmy tu ledwie piątą minutę, wali się w nasze uszy prawdziwa ściana dźwięku.

La. Akustyka zestawu perkusyjnego, dobrze nagłośnionego werbla po lewej, szczękościsk muskanych strun gitarowych po prawej. Ktoś chodzi po pokoju w zbyt dużych butach. Kontrabas grzmi u podnóża wielkiej góry dźwięków. Potencjometry gitarzysty są mokre od potu, zimnego potu. Smyk Duboca wie, co zrobić w takim momencie. Ledwie trzyminutowa miniatura. Trochę jak wstęp do czegoś niezwykłego.

Nuit. Dwa pierwsze fragmenty muzycy grali na podłodze, teraz grzebią się w rozkopanej ziemi i schodzą dużo niżej. Smyczkowa symfonia, upiornie nostalgiczny pasaż grany przez przepitych filharmoników, odrobinę psychodeliczno-deliryczny. Czujemy, którymś z naszych nosów, zapach upalonych rzęs przekwitłej blondynki z bloku obok. Cicha narracja, którą gwałcą pojedyncze akordy werbla, kontrabasu i przegrzanego pieca gitarowego. Demony dość świeżej przeszłości stoją u progu i nie mają dobrych intencji. Tekstura improwizacji jest gruboziarnista – samonakładające się warstwy lepkich dźwięków (tak, tak, znów… dron goni dron). Jakby nowy wymiar akustyki (z czego zbudowane są ściany tego studia?). Krople potu na czołach całej trójki znów mogłyby schładzać szklaneczkę małej szkockiej. Wybrzmienie trzeciej opowieści ma smak niezasłużonej ulgi – torsje gitary, buńczuczność kontrabasu, frywolność perkusji, która niczym tętent koni, prowadzi nas na skraj.

S’ouvre. Gitara Despreza, szukająca wciąż przekornych rozwiązań, nieustannie tyczy szlak tej wędrówki. Jej dominacja rośnie z każdą sekundą tej płyty. Tymczasem pojedyncze akordy kontrabasu Duboca znów zwiastują coś niepokojącego. Preparacje Louteliera zdają się – mimo wszystko – pieprzne i figlarne. Wpadamy do świata dalece pokrętnej sonorystyki. Każdy z instrumentów brzmi jakby inaczej, a jednocześnie każdy z nich wydaje podobne dźwięki. Istotny dysonans poznawczy – umiejętność wskazania źródła pochodzenia danego zdarzenia akustycznego zostaje nam odebrana na wieczność. Genialny wprost moment tego nagrania! Jakże perwersyjna eskalacja! Zmutowany trójdźwięk gitary, kontrabasu i perkusji brnie ku zatraceniu, rwąc recenzentowi nieliczne włosy na głowie. Endorfiny szczytują! Mnogość fonicznych doznań jest tak ogromna, że trudno je ogarnąć, mając do dyspozycji jedynie parę uszu. Finał nie może nie być… dronem. Tylko kontrabas zdaje się być niesforny. Wybrzmienie części czwartej, wybrzmienie całości tej niezwykłej przygody muzycznej, ewidentnie smakuje piekłem, na które nikt tu nie zasłużył. A Desprez i tak, sam jeden, jest tu wielką orkiestrą.

Jeśli ostatnimi czasy słuchałem czegoś równie mrocznego, depresyjnego i dotkliwie pięknego, to była to debiutancka płyta katalońskiego kwartetu Völga. Takie skojarzenie winno tu paść bezapelacyjnie.

Zamiast kupować/ściągać/ pożyczyć od przyjaciela kolejną epokową płytę Joe M., Kena V., Matsa G. czy Petera B. odpalcie Tournesol! Jeśli tylko starczy Wam odwagi, odkryjecie dla siebie wyjątkowy świat akustycznych przyjemności.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Photos de Christian Taillemite sur CitizenJazz (16 avril 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• ★ÉLU★ par Philippe Méziat sur CitizenJazz (16 avril 2017)

Le premier En Corps, par les mêmes musiciens, date de fin 2012, et a été critiqué ici même . Voici donc que se répète le mot de l’amour (« Encore »), ce qui n’a rien d’étonnant en soi, et se souligne dès l’abord visuel par la fleur dressée, très belle figuration du désir, dont on rappelle qu’il est supporté par le même signifiant pour les deux sexes, à savoir le phallus. Génération est un beau sous-titre, qui équivoque sur ce que les corps peuvent produire, mais aussi sur cette génération de musiciens qui, avouons-le, retiennent fort notre attention depuis quelques années.

« Des Corps » connaît son acmé autour de la dizaine de minutes, par l’effet des répétitions que Ève Risser sait si bien conduire en ne donnant jamais l’impression qu’elle joue à insister, par le soulignement aussi de la contrebasse de Benjamin Duboc, pour le coup très linéaire et insistant, par la grâce enfin des frémissements roulants et zébrés d’Edward Perraud. « Des Âmes » vient à point pour rappeler que rien ne les distingue des corps sinon d’en être la supposition de la totalité.

Il s’agit donc rien moins que de se laisser emporter, rouler d’un bord l’autre, sans jamais perdre le souffle ni la texture. Cette aventure à trois se revendique d’un seul principe, qui est l’affirmation de l’Un sous le couvert du pluriel. L’amour que vous portez peut-être à Paul Bley, Charlie Haden et Paul Motian, qui nous ont hélas quittés, se retrouve ici repris, prolongé, magnifié. Si d’autres figures traversent la scène, ne vous en étonnez pas. J’ai seulement nommé celles qui se sont imposées d’abord. L’amour quoi !

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Émission À l’improviste par Anne Montaron sur France Musique (13 avril 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Dave Madden dans The Squid’s Ear (12 avril 2017)

There is an episode of Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations set in Hawaii where the host visits a couple living in Royal Gardens on The Big Island, a subdivision in the path of volcano Kilauea’s three-decade long, lugubrious lava flow. Theirs was the last house that hadn’t been consumed (until 2007 when the owner had to be airlifted from the flame-engulfed area). Daily, they monitored the impending doom and discussed (in a subsequent interview) their relationship with the lava: it was thought of as a living thing, animate, interdependent. But it was / is always still thinking of destruction as it creeped down those hills.

I can’t not think about that lava flow when running through Tournesol (French for « sunflower, » which might make sense to the performers). Guitarist Julien Desprez, contrabassist Benjamin Duboc and Julien Loutelier’s percussion start low in the register and remain in a dark pool with no notions of exploring more than what can be exhausted within this engulfing texture. The bowing (these dudes are big on bowing), grumbling, knob-twiddling and oscillating harmonics of « Pour Que » spend almost seven minutes digging a hole to the center of the Earth; as mentioned, this is dense sound that makes you grit your teeth and brace yourself against a nearing tempest, though the tension rarely releases. « La » is more nervous and percussively dynamic as the trio engages in a twitchy flail out the gate. Loutelier’s sluggish rhythm of cymbal strikes puts the first Western touch-down on the music, but it’s short-lived, and everything returns to vibrating, contained-thunder almost immediately. On « Nuit », the performers operate a physical dragging and droning whisper until a metallic thump from Loutelier encourages all to raise the volume (size and amplitude) while grooving in the same aesthetic. It’s a nebulous shape without seams or borders, skronking and scraping around, that peaks and slowly curls back into a ball in the corner over Desprez’s loop of warm reverb pulses.

Finale « S’ouvre » (yes the four titles spell out « For the night to open ») is a twelve minute summary of the previous events with Duboc hanging back and offering an occasional pluck while guitar and percussion fidget wildly. Not much new, but that’s fine. The music accelerates, develops into an understatedly violent contrabass-lead forest of choking weeds and returns as a wind-blown pile of ash. Lie down and let the last embers char your faculties.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• ★★★★★ par Eyal Hareuveni dans The Free Jazz Collective (12 avril 2017)

The 2012 Free Jazz Collective Happy New Ears! competition was one of the most boring so far. The debut album of the French trio En Corps – pianist Eve Risser, double bass player Benjamin Duboc and drummer Edward Perraud – won the prestigious trophy immediately. It took this unique trio five years to release its sophomore album, recorded at Artacts 16 festival in St Johann, Austria on March 2016, and not because these prolific musicians like to be fashionably late.

Risser, Duboc and Perraud are in-demand musicians who are busy with many solo and side projects.. Risser has worked her White Desert Orchestra (that released its debut album, Les Deux Versants Se Regardent, Clean Feed, 2016), played solo (her debut solo album, Des pas sur la neige, was released on Clean Feed, 2015) and with the duos Donkey Monkey, with drummer Yuko Oshima, and Duo Désordre, with reeds player Antonin-tri Hoang. Duboc kept busy with many small outfits, including trios with guitarist Julien Desprez (from Fire! Orchestra) and percussionist Julien Loutelier (Tournesol, Dark Tree, 2016), sax player Daunik Lazro and drummer Didier Lasserre (Sens Radiants, Dark Tree, 2014), and played in Nicole Mitchell’s Black Earth Ensemble (Moments of Fatherhood, Rogue Art, 2016). Perraud kept working with the trio Das Kapital, his quartet Synaesthetic Trip, duo with vocalist Élise Caron and his solo project Préhistoires.

Generation follows Sun Ra concept of freedom in its special way. Ra, who was skeptical of the common rhetoric about freedom in music, preferred the terms discipline and precision, emphasizing that even the wildest-seeming music requires the implementation of both terms. Generation by no means attempts to be wild-sounding but it certainly offers a bold musical vision, where discipline and precision are essential elements.

Generation expands and deepens En Corps aesthetics from the debut album and offers a similar structure of one long free-improvisation and a shorter one, completely different in spirit. The first piece, the 38-minutes “Des Corps” (Bodies), is a minimalist improvisation that is developed organically through persistent repetitions and delicate alterations of almost transparent clusters of sounds, with a profound meditative impact. The trio moves as a strong, focused unit, never attaches itself to any conventional pulse, and still dances ahead with commanding, powerful conviction. The trio’s intense and balanced interplay patiently opens, with brief solo parts, and gains more power, depth and colors. The second piece, “Des Âmes” (Souls) suggests a haunting soundscape. Risser, Duboc, and Perraud employ a wide array of extended techniques – attaching objects to the piano strings, inventive bowing techniques, including on the cymbals – and sketch a vivid, mysterious narrative that cleverly builds its tension with sudden rhythmic games.

Another masterpiece from En Corps as well from the boutique label Dark Tree. I guess that we already have a strong contender on the this year Happy New Ears! competition.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Joe Free sur Outward Bound (4 avril 2017)

フランスのピアニスト、Eve Risser が参加するトリオ「EN CORPS」の新作が届いている。

イヴ・リッサを知ったのは、3年ぐらい前(だった気がする)メールス中継で観た White Desert Orchestra(昨年11月29日参照)がきっかけだったのだけれど、その後、彼女の他作品を聴くにつれ、ピアニストとしての魅力にも開眼してきた。このトリオは2012年に第1作を出して、本作が5年ぶりの作品ということになるけれど、前作よりもプリペアドピアノの使い方に深化を感じた。透徹した静けさと美しさの中で始まった演奏が終盤、トライアングルが重心に向かってじりじり距離を狭めるように収斂していくさまが実に心地よい。

ちなみにレーベルHPから本作と前作をまとめて注文すると合わせて25%引き(15ユーロ×2×0.75=22.5ユーロ)となり、しかも国際送料も無料となっている。

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Jan Granlie sur Salt Peanuts (3 avril 2017)

Den franske trioen med pianisten Eve Risser, bassisten Benjamin Duboc og trommeslageren Edward Perraud, har tidligere begått platen «En Corps» (DarkTree), som fikk svært gode anmeldelser innenfor den delen av jazzpressen som er opptatt av nyere, improvisert musikk.

Nå er de ute med sin andre trioplate, «En Corps – Generation», som følger godt opp førsteplaten.

Her er det fritt improvisert triomusikk, som i hovedsak befinner seg innenfor den mediterende, mye mer enn den ekspressive delen av improen eller freejazzen.

Pianisten Eve Risser er den som i størst grad drar lasset på de to strekkene «des corps» og «des âmes», og for den som kjenner hennes spill, med unntak av powerduoen Donkey Monkey eller hennes store band, vil forstå hvor det beveger seg på denne innspillingen.

For noen år siden gjorde Risser solokonsert under Kongsberg jazzfestival, og kollega Johan Hauknes var svært klar i sin tale etter konserten, da han proklamerte at Eve Risser skulle spille i hans begravelse. Og det er en mening man mer enn gjerne kan dele med «Høken». Både etter den solokonserten, og etter å ha hørt de to platene med denne trioen.

For det er Risser som er den viktigste musikeren på denne plata. Hennes nitidige utforkning av pianoets klanger, gir en musikk jeg nesten ikke kan huske å ha hørt før. Hun gjør musikken meditativ, på en helt egen måte. Hun er utenpå og inni pianoet og lager lydsammensetninger som innbyr de andre musikerne til også å utforske sine instrumenter på en ny måte. Derfor blir Dubocs tunge, enkle og dype bass-spill et eget kapittel for seg i sammenhengen. Trommeslageren Perraud ligger på topp og leker seg med trommestikkene og trommene på en nennsom, men uhyre effektiv måte, og kommunikasjonen de tre imellom er sømløs og fin.

De to låtene bringer oss rett og slett inn i en helt annen verden enn den reelle vi ser utenfor vinduene, en regntung formiddag i København. Det lydunivers som de tre frembringer er unikt og spennende, og det er sjelden man får muligheten til å høre musikk som er så til de grader intens og samtidig åpen som den vi får på «En Corps – Generation».

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Europe Jazz Media Chart (Avril 2017)

Sélectionné par :

- Rui Eduardo Paes, jazz.pt (Portugal)

- Luca Vitali, Il Giornale della Musica (Italie)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Enrico Bettinello pour Il Giornale della Musica (Avril 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• ★ÉLU★ par Philippe Méziat sur CitizenJazz (12 février 2017)

Deux noms très souvent associés, jusqu’au décès de John Carter en 1991. Dont il me souvient que l’un des enregistrements les plus aboutis de David Murray, Death Of A Sideman, lui était dédié. Chez Mosaic Records on a réédité quelques pièces essentielles des deux compagnons sous forme d’un petit coffret de trois CD. Et voici que, comme une sorte de prélude à un concert de Bobby Bradford (c’était mercredi 1° février 2017, 21.30, au Sunside, avec Vinny Golia, Bernard Santacruz et Cristiano Calcagnile) Bertrand Gastaut a déniché on ne sait où la bande d’un concert de 1975, point d’orgue d’une série de trois consacrés à la clarinette. Après Barney Bigard et Art Pepper, John Carter.

Le jazz en provenance de la côte ouest, surtout quand il est l’œuvre de musiciens africains-américains, met beaucoup de temps à nous parvenir. Quand il nous parvient ! De Bobby Bradford (trompette, cornet) et John Carter (clarinette, saxophone soprano, saxophone alto même dans ses débuts) on sait vaguement qu’ils furent, pour le premier, associé aux premiers travaux d’Ornette Coleman, et pour le second parfois engagé dans les « workshops » de l’AACM. Et si en quartet ils ont pu quelquefois évoquer le « modèle » ornettien (sans piano), de la formation du concert de 1975 c’est une toute autre musique qui surgit, d’abord terriblement engagée, tournoyante, fondée sur les échos et renvois permanents des deux contrebasses, et un drive monumental à la batterie. Puis, au fil des morceaux, les choses s’infléchissent jusqu’à devenir baignées d’une douce lumière, de sons ténus, sensibles, posés avec légèreté dans ce qu’on imagine assez bien d’un rapport intime avec le public. Lequel ne ménage pas son enthousiasme. En fin de compte, une musique intemporelle, un inédit qui vient à point pour compléter un label qui nous a donné déjà tant de belles choses.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Philippe Renaud dans ImproJazz (Janvier 2017)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Tom Greenland dans The New York City Jazz Record (Août 2016)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Andrzej Nowak sur Spontaneous Music Tribune (25 juillet 2016)

Ps. Uwaga! Trybuna udaje się na zasłużone wakacje, w trakcie których nie planuje nowych publikacji (choć licho nie śpi..). Nowych zwariowanych opowieści o jeszcze bardziej zwariowanych muzykach oczekujecie po 15 sierpnia.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• ★INDISPENSABLE★ par Mathieu Durand dans Jazz News (Juin 2016)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• ★★★★1/2 par Eyal Hareuveni pour The Free Jazz Collective (19 juin 2016)

The French boutique label Dark Tree has released so far only five album since 2012, including Tournesol (sunflower in French). But each of these five releases have been carefully-picked, demonstration outstanding form of free improvisation (and modern jazz, considering the reissue of Bobby Bradford & John Carter Quintet, No U-Turn – Live in Pasadena, 1975, from 2015).

Tournesol feature’s the trio of guitarist Julien Desprez, who joined the recent incarnation of Mats Gustafsson’s Fire! Orchestra and is a member of pianist Eve Risser’s White Desert Orchestra; master double bass player Benjamin Duboc, who played on previous releases of the label as the En Corps trio, also with Risser, and another trio with sax player Daunik Lazro and percussionist Didier Lasserre; and percussionist Julien Loutelier, who plays in the quartet of sax player Emile Parisien and pop outfits as Cabaret Contemporain. This trio released a self-produced, digital-only, live album in 2014.

The title of this album may be an apt description to the trio aesthetics. In a similar manner to the sunflower, the trio’s mode of operation is based on the mutual process of floral photosynthesis. The trio is alert to its surrounding atmosphere, feeding from from it and cultivating a rich and independent universe of its own. The four free-improvised pieces of Tournesol were recorded at the same location of the previous album, Ackenbush, in Paris on January 2015.

All four pieces are intense collective researches of electro-acoustic drones, but each one offers a different, coherent, and organically-developed perspective of drone-based textures. The opening track “Pour Que” sounds more industrial and monochromatic with its buzzing hum, but the following, brief « La », already transforms the drone-based texture into a much richer one. It is a minimalist and mysterious soundscape, suggestive in its cinematic qualities.

The almost 13-minute “Nuit” highlights the extended techniques of all three musicians: the commanding bowing technique of Duboc, the gentle and clever play with guitar feedback by Desprez, and the masterful brushwork on the cymbals and drum skins from Loutelier. These techniques form a continuous series of waves of overtones, almost like in an Indian raga introduction, the alap. And as in a raga the meditative introduction intensifies and forms a much more dense interplay, here sounding more claustrophobic, but maintains the trio’s reserved and focused interplay, before it resumes again the meditative-contemplative mode. The final 12-minute “S’ouvre” revolves around assorted rattling sounds of string, cymbals, wood and skins, but, again in a way that suggests clear and tight sonic identity. One that becomes more and more intense, dark-toned, grave without any attempt to offer unnecessary dramatic peaks.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Franpi Barriaux dans Sun Ship (juin 2016)

Ôtez vous tout de suite toute référence à Nana Mouskouri.

Ce tournesol là ne pousse pas dans les champs, il se passe allègrement d’hymne baba au soleil et porte assez mal les robes amples sur des mises-en-plis impeccables.

S’il y a champs, dans la musique du trio Tournesol qui se compose du contrebassiste Benjamin Duboc, du guitariste Julien Desprez et du percussionniste Julien Loutelier, c’est plutôt le champs de ruine ; on s’attend à de la déflagration avec ses trois là, habitué que nous sommes aux traits secs de guitare et aux visites des infrabasses de la contrebasse.

Mais ce qu’on entend là est plus exactement l’après de l’explosion. La matière éparpillée et inerte. Le calme après la tempête. Et même quelques plantes sauvages, des tiges courtes de rocailles et pourquoi pas des fleurs héliotropes qui poussent timidement dans les gravas chauffés à blanc.

C’est ce qu’on entend dans « Pour que » le premier morceau de ce disque enregistré à Akenbush, que le label Dark Tree nous propose aujourd’hui. Du silence impavide, comme figé dans une sidération post-cataclysme, naît quelques griffures. Des gerbes d’électricité caressées comme pour les dompter. Des craquement qui rappelle que l’instrument de Duboc est un être vivant de boyau de métal et de squelette en bois d’arbre à défaut d’être de chair et de sang…

Et puis la percussion de Loutelier, qu’on connaît dans la formation plus pop -foncièrement plus pop- Cabaret Contemporain. Une rythmique soudé à ses complices que rien ne semble troubler et qui fait penser à ce que Darrifourcq pouvait proposer dans le MilesDavisQuintet! dont on n’a pas fini de clamer l’importance.

La musique de Tournesol pousse, s’étend, se tourne vers son point chaud et se répand comme une coulée de métaux lourds chauffé à blanc, à la fois imperceptible et étouffante.

Surtout parfaitement inexorable.

On ne peut rien contre cette musique qui enfle, se divise, multiplie ses cellules, craque parfois comme des bourgeons trop mûrs et fleurissent soudainement sans pour autant n’avoir rien prévu d’autre que de grossir. Ce sont les cordes qui craquent sur « Nuit » et font souffrir le bois à force de pression. Une « nuit » forcément sépulcrale, mais sans dramatisation excessive.

Rien au contraire ne bouge, à peine quelques grouillements microscopiques, ou quelques stridulations irrégulières qui troublent légèrement le mouvement circulaire des percussions.

On est balancé dans un monde infiniment petit où chaque mouvement est imbriqué aux autres. La puissance des musiciens, dans ce qui pourrait être un gigantesque défouloir est au contraire un petit trésor de minutie, où l’attention est extrême, où les instruments parfois se confondent tant les sons tutoient l’étrange et l’inattendu.

Habitué du label Dark Tree, Benjamin Duboc reprend avec ce disque la forme poétique qu’on avait tant aimé dans son trio avec Lasserre et Lazro. L’ensemble des titres des morceaux forment l’incantation « Pour que la nuit s’ouvre » (l’amie Anne Yven vous explique cela très bien…) ; ce n’est pas un haïku ce coup-ci, mais c’est une exploration très sensible des confins de la musique improvisée qui plie mais ne rompt pas. C’est aride, complexe, radical, on songe souvent à certains disques du label BeCoq, mais pour peu qu’on abandonne tout repère, on se laisse vite submerger par cette belle rencontre.

Revenons quelques instants à Nana Mouskouri, qui n’a pas fait que des pubs pour des désodorisants d’intérieur et servi la soupe à la droite grecque :

Le Tournesol, Le Tournesol,

N’a pas besoin, d’une boussole.

Force est de constater que nos trois musiciens non plus. On devrait toujours écouter les grecs (même quand ils chantent comme Nana Mouskouri…). On fait passer le message à la Troïka ?

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Stuart Broomer dans Point of Departure (juin 2016)

“Tournesol” is French for “sunflower,” a potent symbol of light, not something you might immediately associate with the music produced by the band it names, the trio of electric guitarist Julien Desprez, bassist Benjamin Duboc and percussionist Julien Loutelier. It’s dense, darkly resonant work in which the sounds usually associated with the instrumentation rarely occur. That deep resonance is the core, as if the group’s essential instruments were enormous metal bowls and stone cylinders and their inner surfaces were being rubbed to create ringing tones in the lowest register. Circularity, scale and subterranean energy may be the strongest associations with the name, suggestive of a vast underground factory whose purpose seems benign, like the perpetual grinding of a great stone prayer wheel somewhere within the Himalayas.

The CD is brief, some 35 minutes long, but it couldn’t contain more mysterious depth if it were twice that length. Bowed percussion and bass may expand controlled guitar feedback or vice versa, and I have rarely heard electronic and acoustic sound so perfectly integrated. Occasionally a naked snare drum or pizzicato bass breaks in, but it doesn’t stay long. There are four tracks, their titles a divided phrase: “pour que/ la/ nuit/ s’ouvre,” that is, “for/ the/ night/ opens.” I have listened to it repeatedly and believe now that everything has become clear; however, the point of view, the perspective that might organize it and encapsulate it, has disappeared into the music.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Bruno Pfeiffer dans Ça va jazzer (Libération) (31 mai 2016)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Jan Granlie pour Salt Peanuts (19 mai 2016)

Trioen med gitaristen Julien Desprez, bassisten Benjamin Duboc og perkusjonisten Julien Loutelier, er en eksperimenterende combo hvor dronemusikken står i høysetet. De holder til i Frankrike, og er etter hvert blitt viktige personer i utviklingen av denne nye musikkstilen.

Jeg kjenner ikke så godt til dem, men jeg vet at Duboc var med på innspillingen «En Corps», som fikk en viss oppmerksomhet, og han har mer enn nok å henge fingrene i innenfor den nyere, franske jazzen. Julien Desprez finner vi bak gitaren i blant annet Fire! Orchestra, pianisten Eve Rissers White Dessert Orchestra og en rekke andre frittgående prosjekter, mens Julien Lotelier blant annet spiller med saksofonisten Emilie Parisien og Actuum.

Sammen har de her levert fra seg fire strekk som man må være veldig til stede for å få noe ut av. Det er tre megadyktige musikere, med enomt store og lyttende ører, og sammen skaper de en form for dronemusikk som er spennende, men som aldri kommer til å nå de store massene.

Aller helst skulle man vært tilstede på konsert med disse tre. Det er da man får best utbytte av denne, til tider litt stillestående musikken, hvor alt foregår i det stille, med unntak av på sistesporet «s’ouvre» hvor de drar til litt, og hvor instrumenter og lyder glir over i hverandre.

Musikken ville garantert fungert godt i en eller annen skrekkfilm, men å sette seg ned en kveld, med noe godt i glasset og nyte denne musikken, vet jeg ikke om jeg vil anbefale noen å gjøre. I alle fall ikke nå hvor lyset vender tilbake og varmen kommer smygende. Men kanskje til vinteren, når vinden uler på utsiden av huset og det er mørkt.

Men det er flott gjennomført. De lefler ikke med publikum, og står på sitt til siste tone.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Anne Yven sur CitizenJazz (16 mai 2016)

Tournesol a vu le jour il y a déjà quelques années, après la rencontre féconde de défricheurs de sons basés en terres montreuilloises : Julien Desprez, frémissant guitariste, et Benjamin Duboc, profond contrebassiste. Leurs idées et couleurs vibrantes ne prennent pas seulement racine dans leurs chevalets et cordiers respectifs. Ces deux-ci ont été rejoints par Julien Loutelier (membre de Cabaret Contemporain, créateur d’une musique à vocation extatique et hypnotique) dont les percussions, plus caressées que battues, ne pouvaient mieux servir le propos de départ. Après un essai transformé en acte de naissance – une rencontre enregistrée chez Ackenbush, il y a deux ans – la graine était plantée. Il a fallu ensuite s’armer de patience, laisser passer les saisons, afin que le projet mûrisse et satisfasse pleinement ses tuteurs.

Le graphisme de l’héliotrope représenté sur la pochette le suggère, inutile de s’attendre à une déflagration sonore. Tournesol produit une musique centrée et équilibrée, faite d’agrégations et de modulations de matières sonores qui s’influencent et se nourrissent en permanence. Un autre coup d’œil éclairé sur les titres des morceaux, « Pour que », « La », « Nuit », « S’ouvre », achève de démontrer que l’entreprise tout entière est le fruit d’un postulat poétique. C’est d’ailleurs de la littérature, de l’ouvrage Sortir du noir de Georges Didi-Huberman, que Benjamin Duboc a tiré cette phrase éponyme des quatre morceaux.

Cette musique minimale et instrumentale, acoustique et amplifiée, progresse en bourdons insidieux jusqu’à nos tympans curieux. Depuis les profondeurs du sol, d’où elle est extirpée, en direction de l’astre nourricier, Desprez, Duboc et Loutelier la traduisent en sons intrépides. Métaux ou bois, les métonymies sont des figures de proue, les instruments des véhicules pour se mouvoir dans la matière. L’intention avouée est de faire croire que tout jaillit d’une même source. En réalité, ce sont trois paires de mains chercheuses qui jugulent le cours des sons dans l’air, avec une cohésion impressionnante.

La lumière, la vie, ne se manifeste jamais plus brillamment que lorsqu’elle naît du noir le plus profond. Car dès la première écoute, et après plusieurs plongées, la qualité de l’expérience ne semble pas s’éroder. Pas de temps mort : ici, tout vit avec un instinct qui convie l’auditeur à naviguer en sûreté entre perdition et jeu, douleur et chaleur.

« Mes yeux fondirent dans ma bouche, je pris la nuit comme un bateau la mer » : ces mots d’Angèle Vannier, poétesse bretonne, qui les formula lorsqu’elle réalisa sa cécité à l’âge de 22 ans, siéent fort bien à cette musique qui se débat et bat sa mesure, son rythme, dans un temps que l’on verrait infini.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Brian Morton dans The Wire (juin 2016)

Imagine stepping blindfold into a large room and standing among softly growling machines, with maybe something breathing in a far corner. There’s no direct address to the listener as the four parts of « pour que/la/nuit/s’ouvre » unfold. It just emerges almost diffidently. Electric guitar, upright bass and percussion are unidentifiable and indistinguishable in the gentle murk. You feel the parts rather than hearing them separately. And yet, like the (sun)flower of the title – or maybe that’s the group name – this music constantly seeks the light. There’s a tropism towards melody and a governing logic that justifies the conjoined track titles’ hint at continuity. A slow burner, but thoughtful and good.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Mark Corroto sur All About Jazz (3 mai 2016)

The Tournesol the trio is named after is the French word for sunflower, and the the outward appearance of quiet might only pertain to hominid ears. To other plants, bees, and grass, the sunflower is one noisy organism, like huge rotating radio telescopes fighting for the sun’s energy.

Each of the musicians here can be heard in louder, more turbulent ensembles. Bassist Duboc with The Fish (Jean-Luc Guionnet & Edward Perraud), percussionist Loutelier with Stephen O’Malley, and guitarist Loutelier in Mats Gustafsson« s Fire! Orchestra. Here, the improvisations, even though quieter, are just as intense.

Let’s call this screaming plant music. « Pour Que » opens the session with the electric hum and thunder rumblings of some very tight quarters. Its growth may be imperceptible to the unlettered, to us insects, the music portends an ominous event. Listening to this at high volume would certainly attract fans of Lasse Marhaug and Merzbow.

Besides noise, there is also an organic component of animation present here. Bowed bass fertilizes brushwork, and feedback guitar on « Nuit. » The piece levitates upon the galvanized energy of the trio. From the restrained motion, the ferocity increases. « S’ouvre » is to rubbing, like glaciers are to granite. The players massage stings and drum heads into a blossom of energy, culminating in a sundown resolution. If plants could head butt, the tournesol would knock you out.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Chronique par Guy Sitruk sur Jazz à Paris (2 mai 2016)