• Article par Kirk Silsbee dans LA Weekly (5 janvier 2018)

The Century City Playhouse wasn’t much to look at on the outside. The exterior at 10508 Pico Blvd. in Rancho Park was a plain storefront with a marquee. In the late 1970s it hosted a long-running production called Bleacher Bums the way that The Drunkard had been installed for decades at a theater on La Cienega. Inside it wasn’t any flashier — a one-story box with a few rows of old theater chairs. But to the small but vehement army that comprised the SoCal new-music community, the CCPH was the place to be on Sunday nights.

Beginning in 1976, a little golden age blossomed in that matte-black space. UCLA music student Lee Kaplan presented nationally known jazz stars and improvisers, including violinist Billy Bang; trumpeters Leo Smith, Butch Morris, Baikida Carroll, Barbara Donald and Toshinori Kondo; trombonists George Lewis and Benny Powell; woodwind virtuoso Doug Ewart; saxophonists Frank Lowe, David Murray, Oliver Lake, Julius Hemphill, Hamiet Bluiett, John Zorn, Henry Threadgill, Marty Ehrlich, Tim Berne, Evan Parker and Sonny Simmons; pianist Burton Greene; guitarists Michael Gregory Jackson, Eugene Chadbourne, Derek Bailey and Henry Kaiser; bassists Fred Hopkins, Charlie Haden and John Lindberg; drummers Oliver Johnson and Steve McCall; and vocalists Doug Carn, Diamanda Galas and Joan LaBarbara.

He also booked local players — both established and emerging — like cornetist Bobby Bradford; trombonists Glenn Ferris, Bruce Fowler and John Rapson; clarinetist John Carter; flutist James Newton; saxophonists Sam Phipps and Marty Krystall, Frank Morgan and Peter Kuhn; pianist Horace Tapscott; keyboardists Don Preston and Wayne Peet; guitarists Nels Cline, Dave Pritchard and Steve Bartek; bassists Buell Neidlinger, Noah Young, Roberto Miranda, Mark Dresser and Eric von Essen; drummers Alex Cline, Bert Karl and Michael Preussner; dancer Margaret Schuette; and Kaplan himself on electronics.

The larger world kept tabs on the CCPH through Mark Weber’s columns and extended interviews in Coda magazine. An unsigned, quarter-page « Downbeat » feature in the spring of ’79 was accompanied by a Ron Pelletier photo. A KCRW broadcaster, he and Weber assiduously documented jazz and new music around the Southland with their cameras. Under Kaplan’s untiring aegis, Los Angeles became a destination for touring outfits that pursued a left-of-center muse.

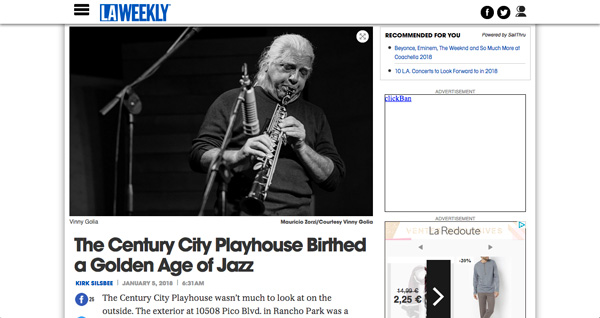

A new Dark Tree CD, Live at the Century City Playhouse by the Vinny Golia Wind Quartet, brings that little epoch back into focus with a previously unissued recital from May of ’79. It complements a previous CD on France’s Dark Tree: Bobby Bradford & John Carter’s NoUturn (’15). The ensemble is woodwind omnivore Golia on several horns, Carter and Bradford, with trombonist Glenn Ferris. The evocative Pelletier photos and Weber’s colorful annotation brings the listener back to that heady and portentous era.

The Golia album catches a developing wind player who seemed to add another horn to his arsenal each time he performed. “#2” combines a typically angular Golia line that moves through a forest of brass and reed voices. The melancholic harmonization of the jagged theme to “Views” clears for a soulful Ferris solo. The better nights at CCPH were made of this.

Bronx-born Golia was a CCPH regular. Kaplan and Nels Cline first met him through their day jobs at the Rhino Records store on Westwood Boulevard. They knew the album covers he designed for Chick Corea’s Song of Singing (Blue Note, ’70), Dave Holland and Barre Philips’ Music From Two Basses (ECM, ’71), and Joe Henderson’s Black Is the Color (Milestone, ’72) but were surprised that he was playing music. In New York Golia had attended clubs and music spaces such as Slugs, drawing and painting to the music. His relationships with musicians like bassist Dave Holland and saxophonist Anthony Braxton encouraged Golia to start working on his own music.

Alex Cline sees two strains that course through Golia’s playing: “He’s very influenced,” he says, “by what the AACM [Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians] was doing in Chicago — playing many instruments and exploring sound through them. The second would be John Coltrane for his relentless exploration on the tenor saxophone.”

The foundation for L.A.’s new jazz that erupted from the ’60s was laid by three Texans: John Carter (1929-91), Bradford (born 1934) and Tapscott (1934-99). Free jazz wasn’t part of any recognized college music curriculum. When Golia began appearing with them at the CCPH with Carter and Bradford, it was a tacit but important endorsement for a young and essentially self-taught musician.

When Bradford returned to L.A. from a year in Europe in 1973, Carter had begun a two-year fling with the soprano saxophone before settling on the clarinet. He would stay with it the rest of his life, extending its accepted range and techniques, developing into an internationally recognized innovator.

Though they maintained their partnership, their visions diverged; that’s where Golia came in. As Ornette Coleman’s original trumpeter, Bradford knew how to play a thematic line and then dive into the musical unknown. Increasingly, Carter’s music often defied notation. “I can’t remember when I first started calling Vinny for a gig,” Bradford says, “but I liked him because he could take the music where I wanted it. John wasn’t interested in playing some of the things I was writing. He didn’t want to play anything with any form — nothing like a tune.”

Golia began his own record label in 1979 to document his own music, but it also became a haven for other players. Scores of releases later, many artists debuted on 9Winds. Golia’s Large Ensemble convenes occasionally; since its beginning in 1982, Golia populates it with interesting players from different areas who often meet for the first time. But his tenure at CalArts has allowed the 71-year-old Golia to help young musicians best realize their goals.

Trumpeter Dan Rosenboom studied with him at CalArts and privately. He leads his own Burning Ghosts band but for the last decade has played in Golia ensembles. “Vinny’s absolutely special,” he declares. “My studies always focused on improvisation. He’d always push me into difficult areas, where I wasn’t very strong. But as soon as I started to get comfortable, he’d take me into another hard discipline. After just a few lessons I had an entirely different way of thinking about composition.”

“Musicians want to be able to speak volumes with one note,” Rosenboom maintains. “Sound is everything to Vinny. He speaks of sounds in terms of colors and he knows that getting deeper into your sound allows you to communicate better.”

The CCPH series closed in 1980, ironically with a band that it had nurtured: Quartet Music, the acoustic cooperative of violinist Jeff Gauthier, guitarist Nels Cline, bassist Eric von Essen and drummer Alex Cline. “Our first concert was the last Century City Playhouse booking,” Alex Cline notes with gravity.

The CCPH is now Pico Playhouse. Lee Kaplan operates Arcana in Culver City, the best arts bookstore in SoCal. Trombonist Glenn Ferris has made Paris his home for decades. Alex Cline extends the legacy in his monthly new music Open Gate concerts at the Eagle Rock Arts Center. Jeff Gauthier founded Cryptogramophone Records (an important local imprint), co-produces the Angel City Jazz Festival and is executive director of the Jazz Bakery. Mark Weber hosts a weekly jazz radio show on KUNM-FM in Albuquerque and maintains his “Jazz for mostly” blog. Bobby Bradford is the Grand Old Man of L.A.’s new music, occasionally convening his Mo’Tet band.

And Vinny Golia continues to teach young musicians at CalArts and season them in his own ensembles.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.